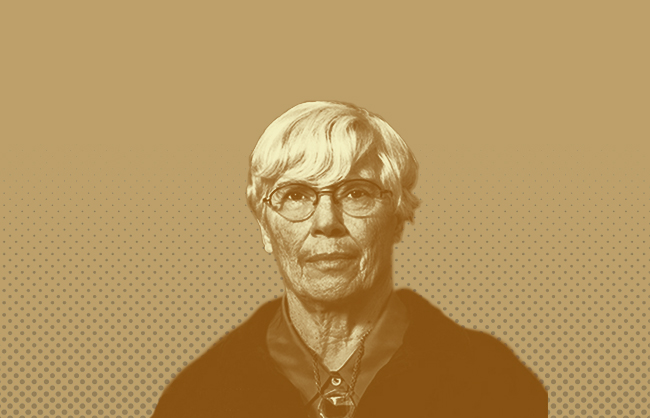

Florence Beatrice Price

Info

Years: 1887-1953

Place of birth: United States

Florence Beatrice Smith was born in 1887 in Little Rock, Arkansas. This era brought with it a social atmosphere that was highly detrimental to the African-American population, as they were subject to laws that advocated racial

segregation in all public institutions. It was within this context that the young Florence was trained as a pianist, organist, and teacher, as well as becoming the first African-American woman composer of eminent distinction.

We suggest listening to the antiphon "Piano Sonata in E minor" while you continue reading:

- Challenges as a composer in a society that rejected her

-

As a woman and an African American, Florence Beatrice Price embodied the antithesis of Eurocentric American creative thought of the first half of the 20th century. She was aware of this fact and unfortunately, the consequences of this reality were borne by her all her life.

What did Florence face when she dedicated her life to the work of composition? The racial and gender stigmas commonly accepted during this period caused Florence to move to places where she could develop her music with some recognition. When she moved to Chicago in 1927, her works began to see the fruits of criticism, promotion and in general, the opportunity. There she found a vibrant community of musicians, composers, critics and patrons who advocated for the success of the African American community. In addition to this collective support, she did not hesitate to demand recognition far beyond; writing letters to distinguished musicians that began with "I have two handicaps, gender and race," pleading for their music to be heard and valued on its own merits rather than on what it represented.

How could his music be listened to without separating it from the prejudices of its author? On several occasions the success of her compositions were considered anomalous. Two of Price's great works were the Sonata for piano and Symphony No. 1 for orchestra, both in the key of E minor and awarded prizes in the Rodman Wanamaker Music competition in 1932 along with another piece composed by her student Margaret Bonds. The victories of these two women were considered to be inexplicable and unrepeatable. - Her compositional voice reflected in the classical style

-

During her training, Florence was sometimes forced to hide her roots. In 1903, when she entered the New England Conservatory of Music, her mother took advantage of her daughter's mixed racial heritage (African, European and Native American) to enroll her with a nationality that was less stigmatized, the Mexican one. However, Florence never forgot her roots and as a composer, she was able to revive the legacy of her ancestors.

Florence's music is an amalgam of traditions

It is a cross between influences that branch off from the folkloric heritage of African origin and the classical tradition of Western Europe in order to create a distinctly American school of music in essence.

Her style clashed with the prevailing aesthetic, whose absolute perspective was the profile of the male and white composer. Samantha Ege, a piano player committed to Price's music and life, wrote these words in her thesis last April about his aesthetics: "Price had no choice but to negotiate the dissonances of race and gender and, as a result, these negotiations are inherent to his compositional perspective and performance contexts" (Ege, 2020).

Price dedicated her work to claiming the voice of his African-American ancestors through the materials, songs and rhythms of black folk traditions inscribed in turn in a structure of classical tradition. These manifestations can be heard in the In the Land O' Cotton piano suite. This suite evokes images of rural life, as well as the melodies, dances and rhythms that motivated the workers on the cotton plantations, such as the so-called Juba1. The melodies are usually lines that seek simplicity and the rhythms are marked by syncopations and oom-pah rhythms that invite the dancer to alternate between tapping his feet on the floor and clapping. In addition, Price's melodies are often impregnated with pentatonic sounds that give us impressionistic colours and only sometimes seem to become hymns taken from the spiritual songs for organ and voice that resonated in the churches. According to Monroe Trotter, one of the first historians of African-American music, "the usually minor character of the melodies has to do with the depression of feeling and anguish, which must always fill the hearts of those who are forced to lead such a life of affliction" (Trotter, 1878).

1 - Traditional African-American dance involves stepping with the feet and clapping on the arms, legs, chest and cheeks turning counter-clockwise. - Precursor and racial symbol

-

Price's compositional voice emerged through crosses in which her artistic, intellectual and cultural vocations converged.

What did she achieve in her struggle to overcome racial walls?

In the 19th century, white women (understanding this concept according to contemporary socio-cultural constructions) were attributed with the inability to compose large forms of music. Based on this fact, we could then assume the scarcity of opportunities and confidence in the abilities of African-American women. In the 20th century, Florence Price would break this racial barrier, opening up space as a composer who risked to defend her culture, whose value was at a much lower level. She was rejected on several occasions because of her race; one of them in her attempt to join the Arkansas State Music Teachers Association. Her enterprising spirit, however, led her to found her own platform, the Little Rock Musicians Club; in which, in addition to developing her facet as a teacher, she had the opportunity to perform her own compositions. Price's musical successes and her courage to continue fighting for her goals were proof of a social progress that resonated deeply in the black communities. Price would become an esteemed figure in the flourishing cultural revolution known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. African-American musicologist and researcher Eileen2 Southern explains how composers like Price were essentially "racial symbols, whose successes were shared vicariously by the great mass of black Americans who could never hope to achieve a similar distinction" (Southern, 1997).

Another moment that made Florence a symbolic figure was her participation with African-American singer Marian Anderson in the 1939 Lincoln Memorial Tribute. Anderson closed the recital with a composition in which Florence Price brought out the black spirit through the melody and lyrics typical of African-American folklore, My soul is anchored in the Lord. Anderson and Price managed to undo in two minutes of music what decades of socio-political inaudibility had done.

Another moment that made Florence a symbolic figure was her participation with African-American singer Marian Anderson in the 1939 Lincoln Memorial Tribute. Anderson closed the recital with a composition in which Florence Price brought out the black spirit through the melody and lyrics typical of African-American folklore, My soul is anchored in the Lord. Anderson and Price managed to undo in two minutes of music what decades of socio-political inaudibility had done.

It became an example for many who had no reference... Florence Price was not simply a racial symbol, but was also a profile that raised the status of the female figure. She and many other women like Estella C. Bonds or Nora Douglas Holt were the example of future generations like Margaret Bonds to feel free to achieve their goals despite gender stigmas. At a time when everything was seen as either black or white, Price's music resonated to defend the ideology of racial supremacy. Unfortunately, even if it resonated with the slogan "Century of Progress", it still had the irony of presenting a black woman as a symbol in the very place where black people were refused entry and women were virtually ignored.

2 - Eileen Southern was an American musicologist, researcher, author and teacher whose research focused on African-American musical styles, musicians and composers. - Catalogue

-

Symphonies

- Symphonie No. 1 in E minor (1931-32).

- Symphonie No. 2 in G minor (c.1935)

- Symphonie No. 3 in C minor (1938-40)

- Symphonie No. 4 in D minor (1945)

Concerts

- Concert for piano in D minor (1932-24); also known as Concert for piano in one movement.

- Concert for violin No. 1 in D major (1939)

- Concert for Violin No. 2 in D minor (1952)

- Rhapsody/Fantasie for piano and orchestra (date unknown and possibly incomplete)

Orchestal works

- Ethiopia´s Shadow in America (1929-32)

- Mississippi River Suite (1934)

- Chicago Suite (date unknown)

- Symphonie Colonial Dance (date unknown)

- Concert Oberture No. 1 (date unknown) based on a spiritual “Sinner, --Please Don’t Let This Harvest Pass”.

- Concert Oberture No. 2 (1943); based on three "Go Down Moses", "Ev'ry Time I Feel the Spirit", "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen".

- The Oak (1943).

- Suite of Negro Dances; orchestral version de Three Little Negro Dances for piano.

- Dances in the Canebrakes (orchestral version of the piece of the same name for piano, 1953).

Choral works

- The Moon Bridge (1930) for SSA

- The New Moon (1930) for SSAA and two pianos

- The Wind and the Sea (1934) for SSAATTBB, piano and string quartet

- Night (Bessie Mayle) (1945) for SSA y piano

- Witch of the Meadow (1947) for SSA

- Sea Gulls, for female chorus, flute, clarinet, violin, viola, cello and piano (1951)

- Nature's Magic (1953) for SSA

- Song for Snow (1957) for SATB

- Abraham Lincoln walks at midnight (date unknown)

- After the 1st and 6th Commandments for SATB

- Communion Service

- Nod for TTBB

- Resignation for SATB

- Song of Hope

- Spring Journey for SSA and string quartet

Voice and piano

- Don't You Tell Me No (1931-34)

- Dreamin' Town (1934)

- 4 Songs, B-Bar (1935)

- My Dream (1935)

- Dawn's Awakening (1936)

- Songs to the Dark Virgin (1941)

- Monologue for the Working Class (1941)

- Hold Fast to Dreams (1945)

- Night (1946)

- Out of the South Blew a Wind (1946)

- An April Day (1949)

- The Envious Wren

- Fantasy in Purple

- Feet o' Jesus

- Forever

- The Glory of the Day was in her Face

- The Heart of a Woman

- Love-in-a-Mist

- Nightfall

- Song of the Open Road; Sympathy

- To my Little Son

- Travel's End

- Judgement Day

- Some o' These Days

Chamber music

- Andante con espressione (1929)

- String quartet No. 1 in G major (1929)

- Fantasie No. 1 in G minor for violin and piano (1933)

- String quartet No. 2 in A minor (published in 1935)

- Fantasie No. 2 in F-sharp minor for violin and piano (1940)

- Quintet for piano in E minor (1936)

- Quintet for piano in A minor

- Five Folksongs in Counterpoint for string quartet

- Suite (Octet) for brass and piano (1930)

- Moods for flute, clarinet and piano (1953)

- Spring Journey, for two violins, viola, cello, double bass and piano.

Piano works

- Tarantella (1926)

- Impromptu No. 1 (1926)

- Valsette Mignon (1926)

- Preludes (1926–32): No. 1 Allegro moderato; No. 2 Andantino cantabile; No. 3 Allegro molto; No. 4 [“Wistful”] Allegretto con tenerezza; No. 5 Allegro

- At the Cotton Gin (1927)

- Scherzo in G (1929 ?)

- Song without Words in G major 1930s

- Meditation (1929)

- Fantasie nègre No. 1 (1931)

- On a Quiet Lake (1929)

- Barcarolle (ca. 1929-32)

- His Dream (ca. 1930-31)

- Cotton Dance (1931)

- Fantasie nègre No. 2 in G minor (1932)

- Fantasie nègre No. 3 in F minor (1932)

- Fantasie nègre No. 4 in B minor (1932)

- Song without Words in A major (1932)

- Piano Sonata in E minor (1932)

- Child Asleep (1932)

- Etude in C major (ca. 1932)

- 3 Little Negro Dances (1933); also arranged for band (1939), for two pianos (1949) and for orchestra(1951)

- Tecumseh (published 1935)

- Scenes in Tin Can Alley (ca. 1937): "The Huckster" (1928), "Children at Play," "Night"

- 3 Sketches for little pianists (1937)

- Arkansas Jitter (1938)

- Bayou Dance (1938)

- Dance of the Cotton Blossoms (1938)

- Summer Moon (para Memry Midgett) (1938)

- Down a Southern Lane (1939)

- On a Summer's Eve (1939)

- Rocking chair (1939)

- Thumbnail Sketches of a Day in the Life of a Washerwoman (ca. 1938-40).

- Rowing: Little Concert Waltz (1930s)

- Ten Negro Spirituals for the Piano1937-42) Let Us Cheer the Weary Traveler; I’m Troubled in My Mind; I Know the Lord Has Laid His Hands on Me; Joshua Fit de Battle of Jericho; Gimme That Old Time Religion; Swing Low, Sweet Chariot; I Want Jesus to Walk with Me; Peter, Go Ring dem Bells; Were You There When They Crucified My Lord; Lord, I Want to Be a Christian

- Remembrance (1941?)

- Village Scenes (1942): "Church Spires in Moonlight," "A Shaded Lane," "The Park"

- Your Hands in Mine (1943) (originally titled Memory Lane)

- Clouds (ca. 1940s)

- 2 Fantasies on Folk Tunes (date unknown)

- In Sentimental Mood (1947)

- Whim Wham (1946)

- Placid Lake (1947)

- Memories of Dixieland (1947)

- Sketches in Sepia (1947)

- Rock-a-bye (1947)

- Three Roses (1949): To a Yellow Rose, To a White Rose, To a Red Rose

- To a Brown Leaf (1949)

- First Romance (ca. 1940s)

- Waltzing on a Sunbeam (ca. 1950)

- The Goblin and the Mosquito (1951)

- Snapshots (1952): I. Lake Mirror (1952), II. Moon behind a Cloud (1949), III. Flame (1949)

- Until We Meet (1952)

- Dances in the Canebrakes (1953); también orquestada.

- Around 70 teaching pieces.

Spiritual arragements

- My soul's been anchored in de Lord (1937), for voice and piano; also arranged or voice and orchestra and for chorus and piano..

- Nobody knows the trouble I've Seen (1938)

- Some o' These Days, for voice and piano

- I Am Bound for the Kingdom for voice and piano (1940)

- I'm Workin' on My Buildin for voice and piano(1940)

- Were you there when they crucified my Lord? (1942);

- I am bound for the kingdom, for voice and piano (1948);

- I'm workin' on my building for voice and piano

- Heav'n bound soldier, for male chorus, (1949)

Organ works

- Adoration (1951).

- Andante (1952)

- Andantino

- Allegretto

- Cantilena (1951)

- Caprice

- Dainty Lass (1936)

- The Hour Glass.

- Hour of Peace or Hour of Contentment or Gentle Heart, (1951)

- In Quiet Mood (1951)

- Little Melody

- Little Pastorale

- Passacaglia and Fugue (1927)

- A Pleasant Thought, (1951)

- Prelude and Fantasie, (1942)

- Steal Away to Jesus (1936)

- Suite No. 1 (1942)

- Memory Mist (1949)

- Variations on a Folksong - Bibliography

-

- https://www.npr.org/2019/08/30/748757267/lift-every-voice-marian-anderson-florence-b-price-and-the-sound-of-black-sisterh?t=1604917061283

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1214357.pdf

- https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/27318/1/Ege_203030808_Thesis.pdf

- https://www.npr.org/2019/08/30/748757267/lift-every-voice-marian-anderson-florence-b-price-and-the-sound-of-black-sisterh

- https://arktimes.com/entertainment/ae-feature/2018/08/30/florence-price-stepped-across-the-threshhold-of-progress

- https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4621&context=thesesdissertations

- https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/27318/1/Ege_203030808_Thesis.pdf

- https://scholarship.miami.edu/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991031447224302976/01UOML_INST:ResearchRepository

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322941421_Florence_Price_and_the_Politics_of_Her_Existence (PDF extracted)

- https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/pqdtopen/doc/1908924625.html?FMT=ABS (PDF extracted)

- Discover more

-

My Soul´s Anchored in the Lord singed by Marian Anderson

We recommend this video in which Samantha Ege talks about four female composers and what they represent for her. Among them is Florence Price with her student Margaret Bonds, Vítezslava Kaprálová and Ethel Bilsland. These four composers were not immune to prejudice, but they were able to find their voice beyond social expectations.