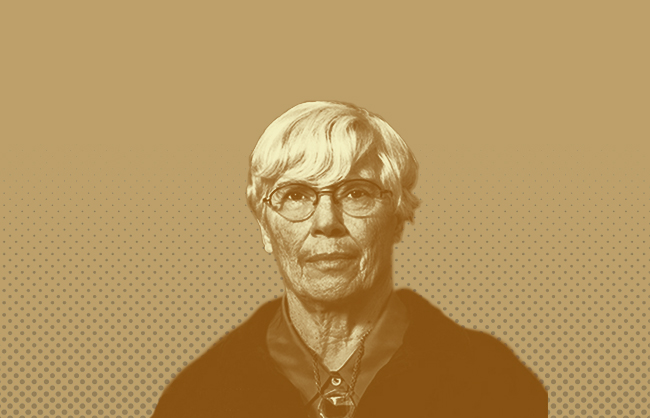

Hildegard von Bingen

Info

Years: 1098-1179

Place of birth: Holy Roman Empire

Hildegard von Bingen was born in 1098 in the village of Bemersheim, Germany, which was part of the Holy Roman Empire at the time. She was a multifaceted abbess, physicist, philosopher, naturalist, composer, poet, and linguist of the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages, where at the age of 12 a girl was already considered a woman - and for many centuries later, at least until the 19th century - the possibilities of destiny were reduced to three places: wife, nun, or servant.

As an abbess, she claimed to have had visions at a very young age, which continued throughout her life. These visions caused her to be treated as a person in connection with the divine, which partly explains how she was able to shed the restrictions of the medieval church on women preachers and pursue philosophy and science.

We suggest you listen to the antiphon "Spiritus Sanctus" while you continue reading:

- Hildegard as a scientific

-

Which scientific achievements are attributed to Hildegard?

It can be contradictory to consider a nun as a scientific woman. But the fact that a 12th-century nun was a doctor is not as surprising as it may seem to us nowadays: for long periods of history, women practiced medicine. She was one of the most reputable physicians of her time and her writings present insights into highly advanced human physiology, the treatment of disease, and the careful analysis of plants, trees, or herbs.

Between 1151-1158 she wrote her work on medicine, entitled Liber subtilitatum diversarum naturarum creaturarum [Book on the natural properties of created things]. She is also the author of the 5-volume long treatise entitled Causae et Curae that includes rudimentary advice, for the care of the teeth or the amenorrhea. Or her most famous work Physica, an authentic treatise on what we would now call natural sciences. -whose real title is The New Books of the Subtleties of the Various Natures of Creatures - includes: 485 plants that it advises to take in minimal doses, such as the medicinal use of precious stones, metals and animals. Hildegard provides a passionate and realistic description of female biological aspects that do not appear in any other medical writing of the Middle Ages and that are an important contribution to gynecology of the twelfth century.

Furthermore, at a time when women's interpretation of Scripture and participation in society was prohibited, Hildegard began writing her first book of visions, Scivias [Know the roads], shortly after her arrival to abbey power but we had to justify her daring in the prologue, ensuring that it was the divine voice itself. The surprising enthusiastic support of the pope and the hypnotic power of her writings made Hildegard from that moment on one of the most influential figures in Christendom (1). Hildegard communicated with the papacy (including popes Eugene III and Anastasius IV), statesmen, German emperors like Frederick I, and other notable figures like Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. Using the support of the Pope, Hildegard decided to leave the dual monastery of Disibodenberg with her nuns to create a new one, exclusively female, where she would develop much of her artistic work.

Despite the fact that these achievements seem to develop naturally and smoothly in the life of this woman, it is necessary to contextualize the historical moment in which they originate. As Marc Bloch states in his work on feudal society (2), this period was the breeding ground for a particularly violent and masculine society. Women suffered the general violence of the time, but rather to a much more complex social fabric, enshrined by the system of laws and religion.

Society showed a clear division into two groups, attending only to the sex of the people, in this way all of them, belonged to the social class they belonged to, was subjected to a situation of inferiority and subordination (3). This provoked the limitation of the presence of women only to domestic spaces and the complete exclusion of public spaces. This submission is due to the system of laws that adjudicated the property of these; first to her father and then to her husband. This fact creates the impossibility for women to have their bodies and the freedom to act at any time. (4)

1 - CASO, A. (2019). Las olvidadas: una historia de mujeres creadoras, Editorial planeta. 2 - BLOCH,Marc (1986). La sociedad feudal,Madrid. 3 - SEGURA, C. (2008). La violencia sobre las mujeres en la Edad Media. Tesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid. 4 - SEGURA, C. (2008). La violencia sobre las mujeres en la Edad Media. Tesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid. - Hildegard as a composer

-

Hildegard wrote more than 150 liturgical compositions, but seventy-seven musical compositions by Hildegard Von Bingen have survived, including a beautiful cycle of songs entitled Symphony of the harmony of heavenly revelations (Symphonia harmonie celestium revelationum) ), a group of eight antiphons that form a narrative about Saint Ursula and a musical drama, the Orto virtutum or Garden of the virtues.

All these works are framed within the scope of medieval monody (that is, groups of voices that sing-along, following the same melody), and written in the forms of the religious lyrical tradition: antiphon, responsory, hymn, and sequence. But her style is very personal, since the melodic line acquires in her works a fluidity and, at the same time, a variety that takes it away from the absorption of traditional Gregorian chant: ranges of two and up to three octaves, ascents and descents in jumps of fifth and melismas (a technique of changing the musical pitch of a syllable in the lyrics of a song while it is sung) that come to include forty or fifty notes in some words, give her compositions a sensitive and dynamic quality (5). These are works that cover wide registers with very elaborate melodies, where music is as important as poetry. This is why it can be said that they constitute constructions like Gothic tracery made to music. These compositions were composed and performed in the Rupertsberg monastery by the nuns of his community. Founded by herself, she developed a large part of her artistic work there, where she teaches that harmony and beauty of the voice were originated in innocence. The relationship between Churches, music and female voice was for a long time very tense. Although in the early days of Christianity both sexes could sing continuously in the temples, as Egeria (Fourth-century Spanish-Roman traveler and writter) recounted during his stay in Jerusalem, from the fourth century on, the pauline idea of female silence also prevailed in relation to song. In the heart of Catholicism, however, the veto was extended - with greater or lesser relaxation depending on the time and place - until the beginning of the 20th century. An example of this is that still in 1874, when Verdi wanted to premiere in San Marcos in Milan the beautiful Requiem Mass that he had composed for the writter Alessandro Manzoni, he found great obstacles from the ecclesiastical hierarchy, which was reluctant to allow the women sing a solemn office in a temple. Throughout all those centuries, the female voice had been replaced in worship by that of children and, since the late Renaissance, in cathedrals and in the richest churches, by that of the castrati. An atrocious custom that where the longest lasting was precisely in the heart of the Catholic Church, the Vatican itself: the white voices of the Papal Chapel were carried out by the castrates (or capons, as they used to be called in Spain) until 1902.

6 - CASO, A. (2019) Las olvidadas: una historia de mujeres creadoras, Editorial planeta. - The voice of a woman on the female gender in the Middle Ages

-

¿ What did she think?

Although it stands to reason that as abbess she would retain her virginity, she may well be the first European woman to describe the female orgasm and advocate for female sexual liberation. Hildegard spoke of sex without fear: in a way that was as clear as it was passionate. She was the first to dare to assure that pleasure was a matter of two and that the woman felt it too. Providing the first description of the female orgasm from a woman's point of view.

In addition to developing an universe map based on a vagina:

Hildegard described man's genitals as a tabernacle, a strong frame, and a ripening flower.

"The wind on his back is more fierce than angry. He has two tabernacles under his command into which he blows like a pair of roars. Those tabernacles surround the stem of all the powers of man, like small buildings set beside a tower to defend themselves. For that reason there are two, so that they can encircle the stem with more force, make it firm, support it and, later, so that they can more strongly and aptly capture the wind that I mentioned previously and attract and emit it in a couple, like a pair of roars blowing together towards a fire. That is when they erect the stem in their possession, hold it tightly. In this way the stem grows through its shoot. “

Hidegard claimed that the sexual act was beautiful, sublime and passionate, which was basically scandalous for the time - 12th century - especially in its religious context. She saw it differently, she could display divinity in people's sex and likewise, she appreciated the urgency of sexual passion.

Hildegard described man's genitals as a tabernacle, a strong frame, and a ripening flower.

"The wind on his back is more fierce than angry. He has two tabernacles under his command into which he blows like a pair of roars. Those tabernacles surround the stem of all the powers of man, like small buildings set beside a tower to defend themselves. For that reason there are two, so that they can encircle the stem with more force, make it firm, support it and, later, so that they can more strongly and aptly capture the wind that I mentioned previously and attract and emit it in a couple, like a pair of roars blowing together towards a fire. That is when they erect the stem in their possession, hold it tightly. In this way the stem grows through its shoot. “

Hidegard claimed that the sexual act was beautiful, sublime and passionate, which was basically scandalous for the time - 12th century - especially in its religious context. She saw it differently, she could display divinity in people's sex and likewise, she appreciated the urgency of sexual passion.

- Catalogue

-

Catalogue

- Symphony of the harmony of heavenly revelations (Symphonia harmonie celestium relevationum) (1150): There are 77 spiritual poems/songs intended for her community in Rupertsberg: 43 antiphons, 17 responses, 8 hymns, 1 kyrie, 1 free piece and 7 sequences for the mass. The title alludes to the celestial songs that Hildegard Heard in her raptures and the wrote them.

- Vistudes Chorus (Ordo virturum) (1150): theatrical representation of a sacred carácter, composed of 82 melodies that describe the struggle between 17 virtues and the devil for the conquest of a soul.

- Your Correspondence (1147.1179)

- Explanation of the Rule of S Benito (Explanatio Regulae S. Benedicti) (1053-65)

- Explanation of Symbol of S Atanasio (Explanatio Symboli S. Athanasii) (1150)

- Canticles of Ectasy: sacred vocal music álbum recorded by Sequenzia ensemble

Manuscripts

Hildergard’s musical works are scattered in six manuscripts and the most important are:

- Dendemonde (Abbey of Saint Peter and Saint Paul) Abteibibliothek, cod. 9 (Codez Villarenser) (contains 57 songs) dated around 1175

- Wiesbaden in the Hessische Landesbibliothek (Riesenkodex- “the gigantic codex”) completed in the 1180s. It contains 75 songs and 30 prose compositions.

- The other manuscripts are, one in Stuttgart and three in Vienna. - Bibliography

- BLOCH,M. (1986),La sociedad feudal,Madrid. CASO, A. (2019) Las olvidadas: una historia de mujeres creadoras, Editorial planeta. SEGURA, C.(2008). La violencia sobre las mujeres en la Edad Media. Tesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid. Victoria CIRLOT [ed.], Vida y visiones de Hildegard von Bingen, Madrid: Siruela, 2009. https://arribayabajoaveces.wordpress.com/2018/03/07/hildegard-von-bingen-una-monja-medieval-precursora-del-feminismo/ https://mujeresconciencia.com/2016/10/03/santa-hildegarda-bingen-religion-ciencia-poder/ http://www.musicaantigua.com/hildegard-von-bingen-una-mujer-excepcional/ https://www.musicaantigua.com/pelicula-vision-la-historia-de-hildegard-von-bingen/ https://www.yorokobu.es/hildegard-von-bingen-orgasmo-femenino/ https://www.musicaantigua.com/la-inspiracion-musical-de-hildegard-von-bingen/ https://web.uchile.cl/publicaciones/cyber/10/ifuentes.htm https://www.bravissimomusica.es/varios-bravissimo/hildegard-von-bingen/ https://www.classicfm.com/composers/bingen/guides/discovering-great-composers-hildegard-von-bingen/ http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/16013/egeria https://culturacolectiva.com/adulto/la-monja-que-explico-el-placer-femenino-y-se-convirtio-en-la-primera-sexologa-de-la-historia

- Discover more

-

The movie: "Vision: The Hildegard Von Bingen Story”